The Adventures of a Clockmaker

Michael Guiver ponders the advantages of old versus modern… Part 1

Like most apprentice clockmakers I served my time at the bench working on English longcase clocks and fusee clocks and indeed, like many of us, these became my comfort zone. (I have to add at this point that being an apprentice in those days meant for the first six months I was tea-boy, sweeper-upper and also spent my time filing and polishing castings until my hands were raw.) As a busy establishment we repaired only antique clocks (not handling anything mass-produced) and also made hand-built clocks from scratch.

Imagine my horror when I was asked to repair my first chiming clock. When placed on the bench it appeared to have arms and legs like a grasshopper and it moved like a half-squashed fly that had just been swatted with a rolled up newspaper.

These days clockmakers seem reluctant to take on the modern longcase clock but it is a very necessary evil unfortunately as so many of them have become treasured, highly esteemed objects. Customers have often paid quite a lot of money for them. These clocks can often cost thousands of pounds despite being made of chipboard or MDF, not to mention the poor-quality movements. Modern chiming longcase clocks seem to be principally made by two different factories producing two completely different movements, the chain wound clock and the cable wound clock. While the latter is the more expensive it is, in my opinion, inferior, usually being overly complicated, not designed to come apart easily (the manufacturers use irreversible circlips) and the poor quality lacquer often suffers in the cleaning tank, which we will talk about later.

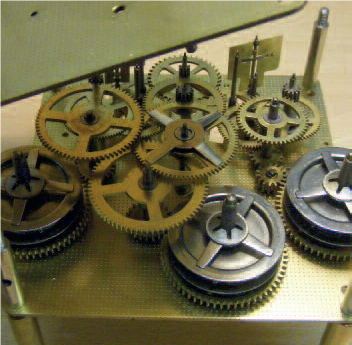

In this article I will deal with the chainwound clock (Photo 1). Although not made from the best materials these clocks are usually reliable and fairly straightforward to repair. The first step is to remove all external parts from both front and back of the movement (Photo 2).

After removing the hammer section and pallets from the back then proceed to remove all of the front work taking great care with the circlips, use pliers very carefully with your finger the opposite side as a guard otherwise they will fly off like tiddlywinks never to be seen again (Photo 3).

Care should also be taken with the two springs shown here namely the rack hook spring and the lifting piece spring: note how the latter is hooked underneath the rack post and on assembly must be gently eased to be underneath the rack tube and not squashed against the plate (Photo 4).

Once the front and back work has been removed then its time to separate the plates – time for a cup of tea now whilst glancing at all of the parts so far placed carefully on the bench remember to label everything as some of the circlips are different sizes. You will note from Photo 5 the brass feet made and secured to the threaded studs which makes the job easier, no balancing on cardboard boxes, etc.

In fact a Photo 1. The chain wound clock at a glance. Photo 2: Starting with the backplate remove all external parts. Photo 4: Watch out for the rack hook coil spring and the lifting piece spring. set can be made for both the front and back of the movement. If you make them out of 3/8 brass rod this is ideal and long enough to cover all protrusions of the movement then the clock can be worked on from either side helping enormously with both dismantling and reassembling. You will also note from this picture the circlip holding the centre wheel as well as the striking intermediate reverser. Don’t forget to put the latter little part in on re-assembly otherwise you will have to start all over again. Next time we will start the repair.

(Photo 3: Taking care with the circlip removal. Photo 5: Separating the plates.)